Why are we so susceptible to the wellness industry and its overpromises?

Lessons from theories of behavioral change.

Today’s article is a bit more contemplative than usual. I’ve been trying to wrap my head around the why behind the success of the wellness industry. Of course, this is more complex than will be covered in a brief newsletter, but I hope it is food for thought.

I don’t have expertise in marketing, and I’m not a psychologist– but I have studied theories of behavioral change in the context of health and science for years. (My doctoral research focused on the ability of graphic cigarette warning labels’ impact on smoking behaviors– which centered around communication of risk tied to tobacco use.)

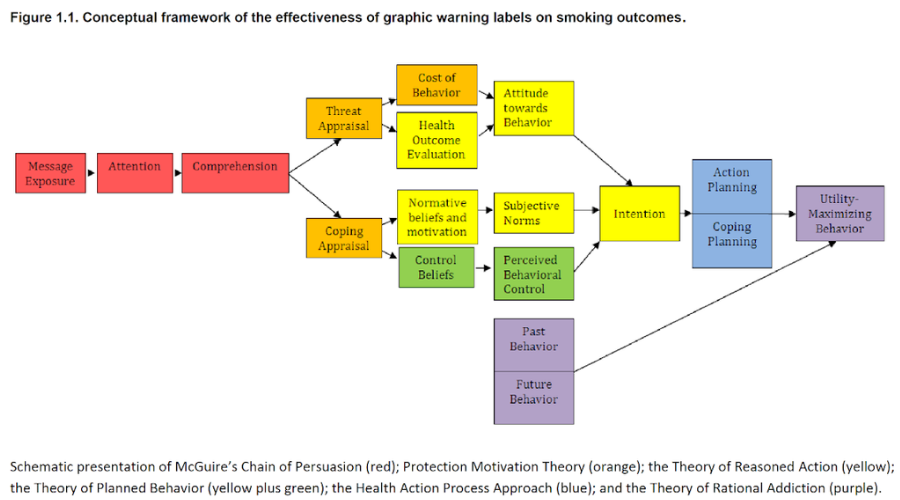

Here’s a little schematic I strung together from multiple theories that illustrates the complexity and multiple factors that influence (and interact) to translate to behavioral change.

Of course, not all are relevant to this conversation since, among other things, there’s the element of nicotine addiction that impacts the effectiveness of graphic labels on cigarette packs to influence behavioral change, but when I stopped to think about it – many of these theories of change are actually quite relevant to a more global conversation about the role of [social] media messaging and the ways we respond to it.

My take is that our desire for control over our health makes us vulnerable to quick fixes promised by the wellness industry and the very absolutist, all-or-none statements made by wellness influencers about what is good for us and what is bad for us.

Let’s discuss this in the context of models of behavioral change:

The Health Belief Model (HBM): When faced with complex health information, people might struggle to feel in control. The HBM suggests that individuals are more likely to adopt healthy behaviors if they believe they can influence the outcome. “Dietary fixes” like avoiding seed oils, for example, offer a clear-cut action– appealing to this desire for control. Even if there isn’t any robust evidence of any actual health harms due to seed oils, the perception of taking a step towards better health provides a sense of agency.

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB): This theory emphasizes perceived behavioral control. Quick fixes might be attractive because they represent a simple action with an immediate sense of control. Taking a daily supplement feels manageable, even if long-term benefits are uncertain. This perceived control can be more appealing than engaging in behaviors requiring more effort or lifestyle changes, like exercising regularly or eating a balanced diet.

The Transtheoretical Model (TTM): People in the pre-contemplation stage might not consider changing behaviors at all. However, a desire for control can make them receptive to messages that emphasize potential negative health consequences. Scare tactics used by some marketers of quick fixes might resonate with this audience. The fear of losing control over their health motivates them to seek a solution, even if it's a quick fix with potentially unproven benefits.

Self-efficacy theory: This theory focuses on an individual's belief in their ability to achieve a health goal. People with high self-efficacy are more likely to engage in long-term healthy behaviors because they believe they can overcome challenges. However, a lack of self-efficacy can lead people to seek external solutions like supplements. Hoping these supplements will provide a shortcut to better health and fill the gap created by a perceived lack of control over their health outcomes through traditional means.

These theories highlight the complex interplay between our desire for control and our health behaviors. Understanding these motivations is crucial for developing effective health communication strategies. Complicating matters is the very imperfect healthcare system that makes it difficult for people to access timely care and limited time with clinicians who are being pressured by administrators to see as many patients as possible and as quickly as possible. Of course people are frustrated and seek out alternatives and become vulnerable to easy fixes.

The wellness industry serves up solutions on a silver platter. It makes very enticing and sexy claims about things that WILL CAUSE CANCER, INFERTILITY, and a whole host of other negative health outcomes. Alternatively, if you TAKE THIS SUPPLEMENT, OR EAT THESE SPECIFIC FOODS… you will reduce cancer risk by X percent!

So, a person who (understandably) wants to live a longer and healthier life (and provide the same to their kids and loved ones)-- will eat that guidance up with a spoon! It gives them control. They have the power to control their health. It is so much more palatable, easy, and actionable than the reality which is much more boring and nuanced and gray. The scientific take is that health is multifactorial, and we know that (with very rare exceptions) nothing we do or consume will drastically impact our health if done so in moderation. (Yes, of course, patterns of behaviors do impact our health– that’s a different topic entirely.)

Ideally, by promoting evidence-based approaches that empower people and increase their sense of self-efficacy, we can help individuals take control of their well-being in a sustainable and healthy way.

Unfortunately, until we crack that code– the wellness industry has us beat. Not only is the wellness industry serving up easy solutions and overpromising on health impacts, but it is untethered by stringent regulations and standards and has grown to be a multi-billion dollar industry that spends its lion’s share of money on very clever marketing. We have to figure out how to get people interested in the nuance of actual health risk– or convince them that all-or-none statements are baseless and undoubtedly oversimplifying complex matters.

P.S. I published an op-ed in The Hill yesterday (yup, a shameless plug, but it’s relevant!) on the ways that misinformation feeds fears about the foods that we eat and has led to a ton of undue anxiety and even disordered eating. Wellness influencers have contributed to countless myths and misconceptions about the safety of ingredients– scaring people away from eating perfectly healthy foods (even veggies and fruits which we typically underconsume). Of course, food is just one of many conduits for misinformation.

I’m going to dig into this topic further but, in the meantime, feel free to reach out to me via the pod page with your thoughts on why we are susceptible to misinformation and wellness myths.