Does the framing of questions about smoking and tobacco use impact patient history?

Read for clinical considerations about smoking and tobacco use

Huzzah! Our very first edition of The Practitioner’s Pulse– a subset of the Unbiased Science Newsletter, intended specifically for the HCP-audience.

Our goal with this newsletter is multi-fold. The information we share may: 1) be specific to healthcare providers and relevant to patient care, 2) be presented at a higher level of scientific complexity that is more appropriate for audiences with advanced education and training in health and science, and 3) help you distill some main takeaways on complex scientific topics for your patients and/or clients.

We have some ideas for initial topics we plan to tackle, but we will also turn to you for ideas and suggestions for content you’d like to see published here.

Note: If you are not an HCP and don’t want to see these types of pieces, just remove “Practitioner’s Pulse” from the sections you want to see in your Substack settings.

To kick off this series, we chose a topic that is near and dear to our hearts: smoking and tobacco use.

For the first decade of my career as a public health scientist, I (Jess) was laser-focused on tobacco control. I was inspired by my dad’s grueling battle with COPD (and later, bladder cancer) to which his two+ pack-a-day smoking habit undoubtedly contributed. He lost that battle in December 2019 and I will never stop raising awareness about tobacco-related issues in his honor.

Assessing smoking status and tobacco use might seem pretty straightforward, but there are some evidence-based tips and tricks for accurately assessing smoking use while taking a history and physical.

When I was a doctoral student in public health, I did an internship at the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene in the Bureau of Tobacco Control. I worked on a variety of projects while at the NYC DOH– analyzing the effect of tobacco taxation on smoking habits and purchasing behaviors as well as the impact of the NYC public parks and beaches smoking ban on number of cigarettes smoked*-- and a project that I spearheaded that explored self-identification as a smoker among non-daily (social smokers). Surrounded by stressed out, overworked grad students who would chain-smoke outside the library in-between dissertation writing sessions, I noticed a trend: these people smoked a significant number of cigarettes, yet almost none of them would say they were a smoker if you asked them.

So I conducted focus groups among undergraduate and graduate students who met certain criteria (smoked at least 1 cigarette on weekly basis but did not smoke daily) across NYC and that confirmed it: even among people who smoked a pack of cigarettes a week, if they did not do so on a regular or daily basis, they did NOT identify as smokers. When asked by a clinician whether they were smokers, the large majority answered no.

(This also meant that smoking cessation and education campaigns were not effective for this sub-group of smokers, which is a story for another time!)

I could write an entire dissertation on this topic (and, as a matter of fact, I did)-- but let’s discuss some key issues:

Taking an accurate history of tobacco use:

So, how can you accurately take a smoking history– including from people who don’t identify as smokers? Don’t ask them if they are a smoker or if they smoke, ask specific questions about tobacco usage.

When is the last time you smoked a cigarette?

How many cigarettes do you smoke, on average, per week or per month?

If they indicate that they smoke 1 or more cigarettes per week, you may wish to follow-up with a question about whether they have smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime.

Some people are surprised to learn about the way smoking status is classified:

Current smoker: An adult who has smoked 100 cigarettes in his or her lifetime and who currently smokes cigarettes.

Every day (aka daily) smoker: An adult who has smoked at least 100 cigarettes in his or her lifetime, and who now smoke at least one cigarette every day.

Former smoker: An adult who has smoked at least 100 cigarettes in his or her lifetime but who has not smoked a cigarette in the last month.

Never smoker: An adult who has never smoked, or who has smoked fewer than than 100 cigarettes in his or her lifetime.

Someday (aka non-daily) smoker: An adult who has smoked at least 100 cigarettes in his or her lifetime, who smokes at least 1 cigarette per week, but does not smoke every day.

There may be some variations on the classifications above, but this is typically how smoking is assessed by the majority of scientific and medical bodies. When it comes to counseling patients who are non-daily smokers, highlighting that they are, in fact, classified as smokers if they have smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime may be quite powerful.

2. Other types of tobacco use and nicotine exposure (other than traditional cigarettes)

E-cigarettes – we have to talk about them because they are booming, especially among youth and young adults. In the US, 25.8% of young adults between 18 and 24 identify as ever using an e-cigarette, making them the largest consumers of e-cigarettes in the country.

Electronic cigarette use is not considered in the definition of current cigarette smoking or any use of tobacco products but many of us argue that it should be. As you know, most e-cigarettes contain nicotine. While e-cigarettes may be less harmful than conventional cigarettes (which have the added harms of combustion)-- they are certainly not harmless. So, it is helpful to remind e-cigarette users of the impacts of nicotine in and of itself.

Once nicotine has entered the body, it is distributed quickly through the bloodstream and crosses the blood–brain barrier reaching the brain within 10–20 sec after inhalation. Once in the brain, it binds to its target, the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR), which take part in cholinergic signaling in the prefrontal cortex (PFC).

Young brains (teens and adolescents) are especially vulnerable to the effects of nicotine. The PFC is the brain area responsible for executive functions and attention performance, is one of the last brain areas to mature, and is still developing during adolescence.

Nicotine impacts (and slows) wound healing and impairs immune system function. It does this in a few ways:

Smoking not only reduces white blood cell migration to the wound site, but also diminishes lymphocyte function, cytotoxicity of natural killer cells, macrophage sensing of gram-negative bacteria, and the bactericidal activity of neutrophils.

Smoking is also associated with a reduction in fibroblast proliferation during the proliferative stage of wound healing. Fibroblasts produce essential structural proteins such as collagen fibronectin that are needed for granulation tissue formation and epithelialization. Collagen is the primary structural protein that affects a healing wound’s tensile strength and research has demonstrated that its production is diminished in smokers.

Please note: there are also other types of tobacco and nicotine use (each with its own risks), including hookahs and waterpipes, cigars, chewing tobacco, snuff, snus, cigarillos, and more. Certain cultures are more likely to consume tobacco and nicotine via these modalities and should be a consideration when taking a patient’s history.

[Not-so-] Fun Fact: In a typical 1-hour hookah smoking session, users may inhale 100–200 times the amount of smoke they would inhale from a single cigarette. In a single water pipe session, users are exposed to up to 9 times the carbon monoxide and 1.7 times the nicotine of a single cigarette.

3. Evidence-based treatments for tobacco and/or nicotine use

It’s estimated that less than 10% of people who try to quit tobacco succeed without a quit-smoking product. Many more succeed when using one, and the odds of successfully quitting are even higher when you combine counseling with one or more quit-smoking products.

There are two main types of cessation products:

1) nicotine replacements (patches, gum, etc.) and 2) prescription medications. Both can help manage cravings and withdrawal symptoms, boosting your chances of success. E-cigarettes, though often used for quitting, lack FDA approval, and we’ll address that in a separate section.

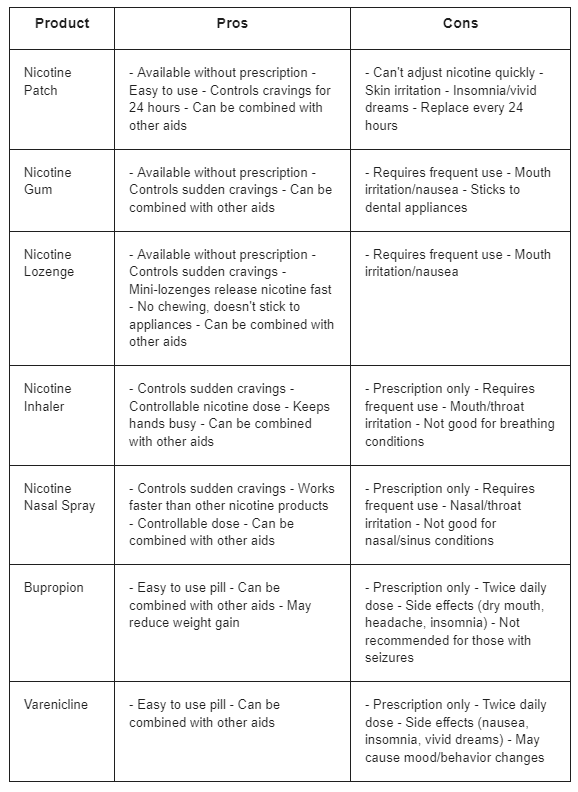

We summarized some commonly used quit-smoking products and their pros and cons, below:

Worth noting: Cytisinicline (historically known as cytisine) is a naturally occurring plant-based alkaloid that binds selectively to nicotinic receptors in the brain that regulate nicotine dependence, alleviating the urge to smoke and reducing the severity of nicotine withdrawal symptoms. Its mechanism of action is similar to that of varenicline, an FDA-approved smoking cessation aid. Though cytisine has long been popular in Eastern Europe and became available in Canada in 2017, it's not sold in the US. Large clinical trials are underway in the US that may lead to its FDA approval in the near future.

It’s difficult to tease out the effectiveness of these products since success can vary greatly depending on individual factors like:

Severity of smoking habit and level of addiction

Underlying health conditions (some medications might not be suitable for certain conditions)

Personal support and commitment (success often relies on behavioral changes alongside the product)

Study methodology and population differences (success rates reported in various studies can differ based on specific parameters).

However, researchers at UCSF have come up with the following general success rates for each cessation tool:

Self-Help: Quit Rate 9-12%

Counseling: Quit Rate 13-17%

Bupropion SR (Zyban): Quit Rate 24%

Nicotine Replacement Therapy: Quit Rate 19-26%

Varenicline (Chantix): Quit Rate 33%

Medication Combinations: Quit Rate 26-36%

Counseling and Medication Combinations: Quit Rate 26-32%

When counseling your patients, it is helpful to understand the facets of their addiction– is it driven primarily by nicotine dependency, is it an oral fixation, is it simply the habit of taking breaks and stepping outside to smoke? Understanding the primary drivers of their tobacco/nicotine use is critical for effectively addressing their habit and helps you advise them on which cessation tool they should consider as a starting point.

The use of e-cigarettes as a cessation tool

The use of e-cigarettes as a cessation tool is quite controversial– this is exacerbated by mistrust of the Tobacco Industry which is, of course, trying to sell its products and is not concerned about helping people quit.

Some argue that it is highly effective while others say that many users end up relying on both cigarettes and e-cigarettes, hindering their progress. Some studies have found e-cigarette use was associated with an elevated risk of initiation of combustible cigarettes. (This is also a huge issue for youth and young adults who start out smoking e-cigarettes and may “graduate” to smoking combustible cigarettes).

Back to using e-cigarettes as a cessation tool for current smokers– a recent Cochrane review found that people are more likely to stop smoking for at least six months using nicotine e-cigarettes than using nicotine replacement therapy, or e-cigarettes without nicotine, and that nicotine e-cigarettes may help more people to stop smoking than no support or behavioral support only.

Bottom line: If you recommend e-cigarettes to your patients who are smokers, you should monitor their use carefully and ensure that the e-cigarettes are not actually exacerbating their nicotine dependence. It is also important to advise against long-term co-use of e-cigarettes (instead, e-cigarettes should be a way for them to wean themselves off of smoking cigarettes).

Remember, you have a lot of power and influence as a clinician (much more so than we do as scientists). Even simple interpersonal / communication skills like eye contact, empathetic listening, and motivational interviewing can go a very long way when it comes to helping your patients break their smoking habit.

P.S. We have a two-part episode series on e-cigarettes and vaping!

Part one:

Part two:

In memory of my father, Jeff Steier. Watching how hard he fought the effects of smoking on a daily basis has inspired my commitment to conducting research on tobacco control policies and cessation tools in the hopes of preventing others from battling smoking-related disease.

-Jess