Do you need to throw out your Cheerios and Oats?

Not so fast! A pilot study by the EWG has caused many people to unnecessarily go honey nuts over Chlormequat concerns.

Did anyone else snarf their Cheerios this morning when reading the latest results from the pilot study by the Environmental Working Group (EWG)? We will summarize why you should not throw out your Cheerios and Quaker Oats despite the splash this is making in major media outlets which has caused a lot of fear and concern among cereal lovers!

We dropped an Instagram post today, but let’s do an even deeper dive!

What is chlormequat and why is it used? Chlormequat, also known as chlormequat chloride, is a chemical discovered in the 1950s that is used to block the gibberellin hormones that stimulate growth. This helps to shorten and strengthen the stems of crops like wheat, oats, and rye. By preventing plants from bending or "lodging” (the bending over or breakage of small grain stems) chlormequat can prevent severely limited grain yields, and improve harvestability, and overall grain quality. Chlormequat has been used by farmers around the world for decades. US farmers have recently been advocating for its use as a tool to help them make it more efficient to harvest grains and to potentially improve crop yields in the face of increasingly severe weather events related to climate change.

Why is Chlormequat on the radar of the EWG? The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has historically restricted the use of chlormequat to treat ornamental plants like geraniums, poinsettias, begonias, osteospermums, and hibiscus plants. Chlormequat was not approved, before 2023, for use on food crops grown domestically in the US - despite being used on grains in the United Kingdom, European Union, Canada, and other countries for decades. In 2018, the EPA did allow for a provision for chlormequat residues to exist on imported oats and other foods from Canada, and the allowed residue levels were further increased in 2020. Importantly, chlormequat is currently being evaluated by the EPA for use on food crops in the US per a memorandum issued in April 2023 Supporting the Proposed Registration Decision to Approve the First Outdoor Food Uses on Wheat, Triticale, Barley, and Oats for Chlormequat.

The EWG has taken a strong stance against imported foods containing residues of chlormequat (starting in 2018) and has particularly ratcheted up its efforts since April 2023 when the EPA made the provisional recommendation to allow the use directly on crops like wheat, triticale, barley, and oats by US farmers.

The EWG has a long history of aggressively challenging industry standards, farming techniques, and government legislation. They have faced a great deal of criticism for their scientific methods and exaggerations of toxicological risks. The group is deeply involved in the movement to advance organic food, and they have been criticized for emphasizing pesticides out of proportion to the benefits of eating a balanced diet rich in fruits and vegetables (organic or not) along with the benefits of sustainable farming practices to combat the effects of climate change.

How can I understand the study from EWG that has created all this confusion & concern? The recent pilot study conducted by the EWG has two elements – (1) testing the residual amounts of chlormequat in 25 wheat and oat-based products in US supermarkets and (2) testing the amount of chlormequat that was detectable in a very small sampling of human urine samples in three geographic locations – Florida, South Carolina, and Missouri.

Wheat & oat products – this pilot study found that many products had non-detectable (ND) amounts of chlormequat and in the “worst” case sample had 291 ppb (parts per billion) of chlormequat residue. NOTE: It's worth clarifying how this 291 ppb compares to allowable levels as set by the EPA. The EWG group concluded, “They observed high detection frequencies of chlormequat in oat-based foods.”

Urine samples – they also collected 96 “convenience samples” across the three states, some were found to have ND amounts and some had detectable levels (maximum 52.8 μg chlormequat per gram creatinine) with a detection level ranging from 69-90% in the populations sampled. They concluded that “four out of five sampled had some detectable chlormequat levels - some of which were significantly higher in samples collected in 2023 compared to earlier years.”

The EWG highlights and summarizes several toxicological studies conducted in animal models (specifically mice & pigs) with mixed methodologies. They suggest that exposure to chlormequat can reduce fertility and harm the developing fetus at lower doses than those used by regulatory agencies to set allowable daily intake levels for humans.

Overall, they concluded that the current exposure levels they detected in the pilot study called for “more expansive toxicology testing, food monitoring, and health studies in humans to understand the health effects of chlormequat.”

Should we throw out our Cheerios?Not so fast. This was only a small pilot study with a methodology that is not particularly robust and given the results provided, drastically overstated the risk to humans. Again, the EPA and other agencies closely monitor the safety of the ingredients in our foods. While animal studies are important precursors to human studies that help us identify potential safety signals, there is no indication that chlormequat poses harm to humans. Additionally, finding a chemical doesn’t automatically equate to findings of harm. And while the EWG may routinely like to target artificial pesticides, we have to remember basic toxicology: that the dose makes the poison and that a chemical being natural versus synthetic tells us nothing about how dangerous it is. All chemicals (man-made or natural) can be harmful at a certain dose. But our bodies excreting miniscule volumes of residual pesticides in reality should show us how well our bodies are working and how little chemical remains in respect to consumer exposure.

When ingested, Chlormequat is completely absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract (maximum concentration in plasma after 2 hours). Approximately 95% of chlormequat is removed rapidly by the body (within 1-2 days) and is excreted undegraded in the urine (75-85%), but also via feces and bile. It is not metabolized by the body and there is little to no evidence to date that shows that there is any accumulation in the human body and specific organs (e.g., liver, reproductive organs, fatty tissues).

The EWG noted in their own publication that the “current chlormequat concentrations in urine from this study and others suggest that individual sample donors were exposed to chlormequat at levels several orders of magnitude below the reference dose (RfD) published by the US EPA (0.05 mg/kg bw/day) and the acceptable daily intake (ADI) value published by the European Food Safety Authority (0.04 mg/kg bw/day).”

Additionally, when looking at the cereal and oats samples taken, it is important to put into context the dietary allowances set by the EPA to determine acceptable levels of both acute and chronic dietary ingestion of chlormequat (see Table 1 for full guidance). All these guidelines and toxicity calculations can be very daunting and are not easy for everyone to understand (especially the media who did not do this topic justice), but we will try to explain it below.

Table 1: A summary of the chlormequat chloride toxicological doses and endpoints used in the referenced human health risk assessment

The above was recreated from the EPA Registration Proposal (April 2023).

Given all this information, how do we calculate risk in humans?

The no-observed adverse-effect level (NOAEL) is defined as the highest dose examined in all collective toxicologic studies to date that produced no detectable adverse effect on test animals. To translate the NOAEL from the animal toxicity studies to a numeric value protective of human health, the EPA applies a safety factor to the NOAEL. Typically, a value of 10 is used to account for extrapolations from test animals to humans and another safety factor of 10 is used to account for sensitive subpopulations to give a total safety factor of 100 (10 × 10). In other words, the NOAEL is divided by 100 and the resulting value is referred to as the reference dose (RfD) for the compound of interest – in our case chlormequat.

The population-adjusted dose (PAD) is an even more conservative measure when compared to the RfD and ADI as it accounts for additional population-level variability in sensitivity to chemicals (e.g., infants, children, and women who are breastfeeding). This means that beyond the RfD and ADI, a sensitivity coefficient is used to add even more safety buffers to calculate the risk in these populations.

In the case of chlormequat, the NOAEL level for acute chlormequat exposure is 100 milligrams per kilogram body weight per day (mg/kg/day), and chronic exposure is 5 mg/kg/day. Then with the additional safety and sensitivity coefficient (PAD), we arrive at:

o The acute population adjusted dose (aPAD) for chlormequat at 1 mg/kg/day.

o The chronic population adjusted dose (cPAD) for chlormequat at 0.05 mg/kg/day.

Both PAD values are 100 times lower than their respective NOAEL levels, meaning they are extremely conservative.

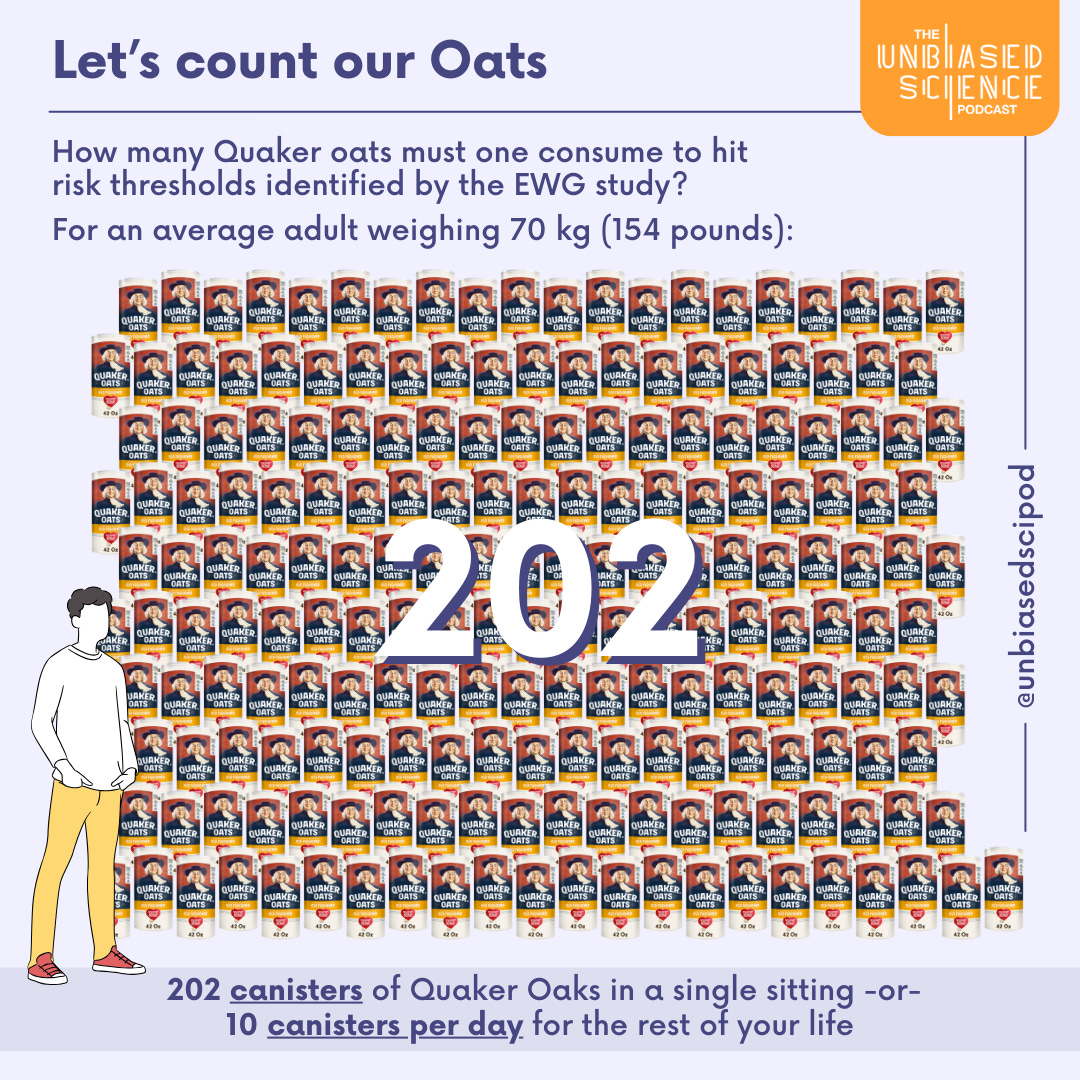

Let’s count our Cheerios and Oats, shall we?

Taking what we discussed above regarding the risk calculations, we summarize for an average adult weighing 70 kg (154 pounds) how many canisters of Quaker oats or boxes of Cheerios they must consume based upon the EWG study to reach toxic levels set by the EPA (See Table 2). As you can see, as an adult, you must consume 202 canisters of Quaker Oaks in a single setting or 10 canisters daily for the rest of your life to reach toxic levels given the highest trace amounts noted in the EWG study (291 ppb). Whereas for Cheerios, you must consume 1647 boxes in a single setting or 82 boxes daily for the rest of your life to reach the toxic levels given for the highest trace amounts noted in the EWG study (107 ppm)

For children, oat consumption starts at 6 months of age, whereas on average Cheerios start at 10-12 months of age. As such, the weights were adjusted to be as conservative as possible in illustrating the risk with the extremely conservative PAD toxicity levels. The number of canisters and boxes is less than adults, but even the hungriest child could not consume the amount of oats or Cheerios to exhibit the toxicity levels that would be considered harmful in humans.

Why do we rely on animal models for this toxicity?

Before release, xenobiotics like chlormequat are assessed in different model animals for potential toxic effects on human health including reproduction and embryo/fetal development. Various endpoints are used to assess for such adverse effects, e.g., testicular histopathology and sperm evaluation in males, estrous cycles, follicle count, evaluation of oocyte maturation as well as pregnancy rate and litter size after natural mating in females.

The EPA and other agencies closely monitor the safety of the ingredients in our foods. While animal studies are important precursors to human studies that help us identify potential safety signals, there is no indication that chlormequat poses harm to humans. The EPA’s recent human health risk assessment found no dietary, residential, or aggregate (i.e., combined dietary and residential exposures) risks of concern. Importantly as well, the EPA’s ecological risk assessment identified no risks of concern to non-target, non-listed aquatic vertebrates that are listed under the Endangered Species Act, aquatic invertebrates, and aquatic and terrestrial plants.

That being said, our present practice of using guideline animal studies on single chemicals to set tolerance levels does not address the fact that most humans carry evidence of multiple chemical exposures and mixture effects. A forward-looking approach (especially for reproductive effects) involves a more careful exploration of adverse outcome pathways through untargeted exposure analyses and metabolomics. As with all things, the data and evidence may evolve just as the animal data has already done surrounding chlormequat in animal models.

Other references that may be of interest, showing no impact on mammalian fertility:

1. Sorensen MT, Danielsen, V. Effects of the plant growth regulator, chlormequat on mammalian fertility, Int J Androl. 2006;29;129-33

The study assessed 48 pigs used with a control. In vitro studies showed effects on male sperm, but this was not replicated in live animal models.

2. Sorenson, MT, et al, No effect of the plant growth regulator chlormequat on boar fertility. Animal 2009;3;697-702

Assessed chlormequat at levels up to that acceptable for humans on reproduction in male pigs (boars). Researchers studied 6 boars in three treatment groups: 0 mg CCC/kg BW per day (control), 0.025 mg CCC/kg BW per day, and 0.05 mg CCC/kg BW per day. Chlormequat could not be proven to be detrimental to the selected reproduction traits in male pigs

Tested a mouse in vitro fertilization/in vitro culture (IVF/IVC) system to assess other aspects of reprotoxicity of xenobiotic exposure. Two pesticides, vinclozolin (V) and chlormequat (C) were added to feed in low (40 and 900 ppm, respectively) and high (300 and 2700 ppm, respectively) doses and compared to control (nil pesticide).

Key points to remember:

o A pilot study is a small-scale preliminary study typically conducted before a larger research project begins to check the feasibility or improve the future research design. Unfortunately, the use of this type of study by the EWG was done to generate data that is overly complicated for most of the population to understand but can successfully be used to drum up negative attention and concern in the media and society.

o In evaluating the chlormequat registration application, the EPA assessed a wide variety of exposure information (i.e., where and how the pesticide is used), the environmental fate (i.e., how the chemical will move and persist in the environment), and toxicity studies (i.e., effects on humans and other non-target organisms) to determine the likelihood of adverse effects (i.e., risk) from exposures associated with the proposed use of the product. The EPA was confident with the information gathered over the past decades around the world and in clinical studies in animals to date regarding the safety profile of chlormequat.

o In accordance with the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA), the EPA registers a substance like chlormequat when it determines that it will not cause unreasonable adverse effects on humans or the environment while considering the economic, social, and environmental costs and benefits of use. Under FIFRA, the EPA is charged with balancing risks posed by using chlormequat against its benefits and must determine if the benefit of its use outweighs the risks for the EPA to register a chemical like chlormequat for use in the US.

o The authors of the EWG do not discuss the potential bias and limitations to their study - including the sample selection being small and one of convenience, no known demographic background provided on the patients e.g. body weight, dietary patterns, recreational hobbies including gardening, etc. and the increase importation of Canadian wheat into the US starting in 2018 that could also contribute as well to their chlormequat levels.

o Additionally, the tests the EWG used are extremely sensitive to detecting any levels of chlormequat – in this case in the parts per billion (ppb). Just because you can detect it, does not mean it is harmful unlike what the EWG implies.

Monitoring by governments and scientists is the responsible thing to do and helps us build the repository of knowledge and science around this topic, so any calls to continue research and to ensure the safety of chlormequat are reasonable. But terrifying people into thinking they will die eating their cereal with a poorly conducted study is not how we as a scientific community should tackle this particularly important topic.

Do better EWG – the dose makes the poison!

Special thanks to Michelle Bridenbaker for co-authoring this newsletter, and to Drs. Nicole Keller, Chris Weis, and Stuart Batterman for reviewing and/or contributing content.

If you are a healthcare provider and want to have access to clinically relevant content, please feel free to add your name and contact information to our ListServ here.

As always, please share our newsletter with your friends and family. We will never waver in our commitment to providing critical analysis of scientific evidence!