Covifenz: the world's first plant-based COVID-19 vaccine

This technology is easily scalable, cost-effective, and has the potential to speed vaccine development

4 minute read

A new COVID-19 vaccine has been approved recently by Health Canada. Covifenz, also called CoVLP, MT-2766, or Plant-based VLP, is the first plant-based COVID-19 vaccine. Made by Canada-based company Medicago, this vaccine has shown similar efficacy to other vaccines currently available. Canada is also urging the WHO to approve it so they can donate via COVAX - the worldwide initiative for equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines. This vaccine is currently undergoing clinical trials in several other countries around the world.

Let’s talk about the technology, and how we are able to produce a vaccine in plants.

Their unique technology is different from the main players we’ve seen to date in the COVID-19 vaccine line-up.

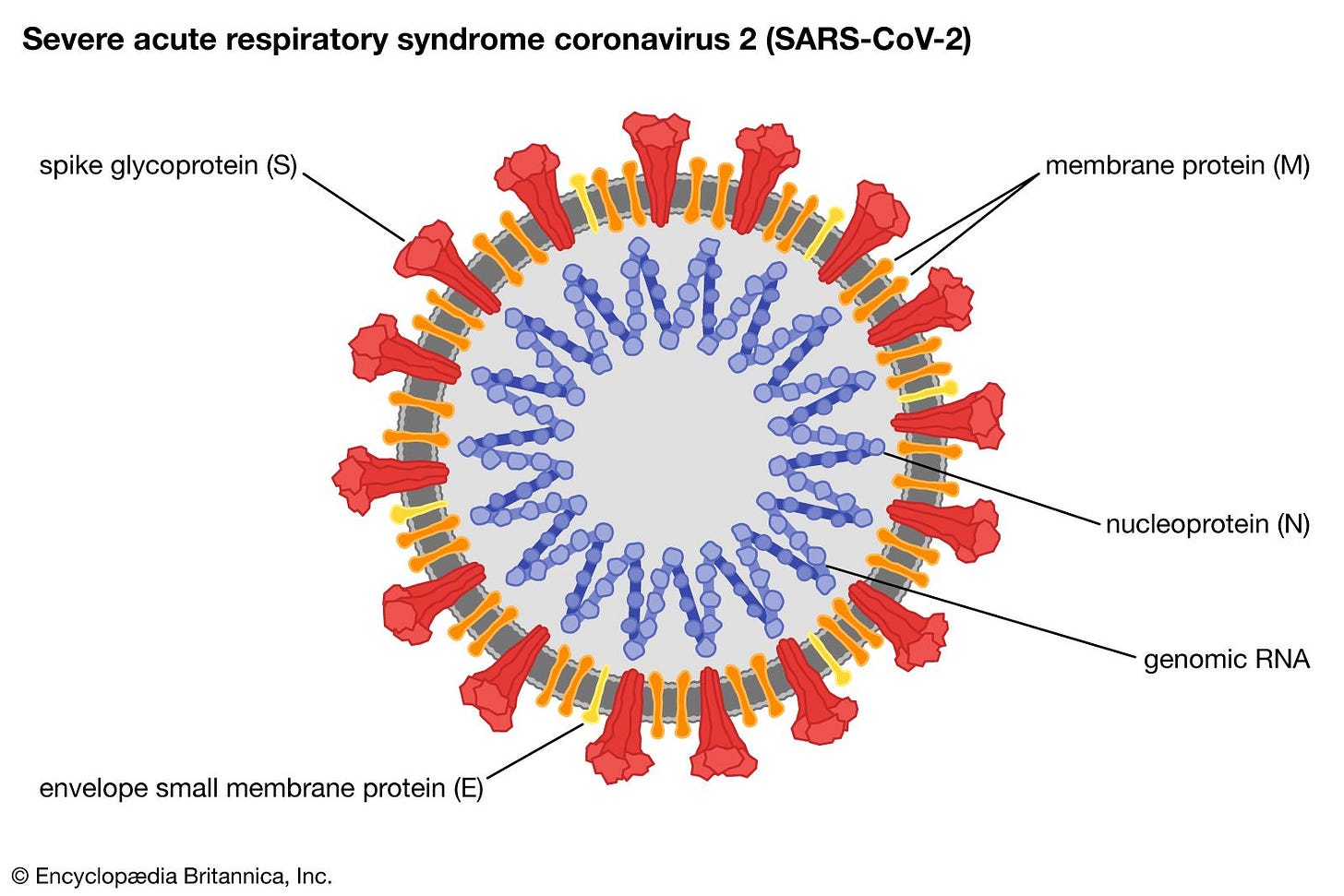

To create any vaccine, you must create some sort of particle that will be recognized by the immune system as foreign and stimulate a subsequent immune response. These particles use an antigen - which is a molecule that leads to the production of antibodies by our B cells. Antigens are often proteins, but can also be sugar molecules or lipids. For COVID-19 vaccines, the antigen that has been used so far is the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2; this is a key protein that is required by the virus to infect ourselves, and is also displayed on the outside of the virus and interacts with our immune system.

The antigen may be an ingredient of the vaccine itself (such as the case in live-attenuated, inactivated, purified antigen, or toxoid vaccines), or it can be created by the body via a messenger sequence encoding the antigen in the vaccine (mRNA vaccines, for example).

In the case of Covifenz, the plant Nicotiana benthamiana (a close relative of the tobacco plant) behaves as a bioreactor to synthesize the antigen, which are termed virus-like particle (VLPs).

How does this work?

First, a naturally occurring soil bacteria (Agrobacterium tumefaciens) is genetically engineered to contain the gene and ultimately produce the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2.

Next, the bacteria are mixed into a solution in order to deliver the spike protein gene to plants. Remember, plants absorb water/fluid through the soil which is critical for photosynthesis - the process by which plants generate their own nutrient sources and ultimately grow. Substances contained in the fluid absorbed by plants are incorporated into new plant growth.

Third, the plants are submerged in the “bacterial bath” and liquid containing bacteria is absorbed by the root system of the plants. The plants are returned to the greenhouse and allowed to grow normally for a minimum of 4 days. During this period, the plants are synthesizing new plant cells after incorporating the genetically engineered bacteria. As a result, as the plants are growing, they are also producing large numbers of the virus-like particles (VLPs): the spike protein code that was delivered by the soil bacteria.

In this way, the plants act as bioreactors: a term used to describe a vessel (or organism) that is able to carry out biochemical processes. In the lab, these are often cell culture systems; so in a plant, the plant itself is working as a culture system. This is similar to the process used to produce influenza virus vaccine, where chicken eggs are used to produce large amounts of influenza virus.

After the plants are allowed to grow, the leaves are harvested from the plants and homogenized into a solution. From there, the VLPs are extracted and purified (this is the active ingredient of the vaccine). The VLPs are then combined with an adjuvant, which is a substance added to a vaccine to improve the immune response without increasing the dose of the active ingredient, in order to formulate the vaccine. The adjuvant used is GSK’s pandemic adjuvant. These particles are recognized by our immune system as a virus from which it needs to be protected, but they do not contain the core genetic material, so they are non-infectious.

Since these VLPs are grown in plants, this process is easily scaled up as the plants themselves can produce large numbers of VLPs. As such, this method is extremely cost-effective and has the potential to speed up development processes of vaccines. In addition, the vaccine itself is refrigerator stable, making it attractive to the global community that may not have access to more stringent storage that is required for some other COVID-19 vaccines.

The vaccine itself is administered as 2 doses 21 days apart. Each dose contains 3.75 micrograms of virus-like particles (VLP) of SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) protein (original strain) and 0.25 millilitres of the AS03 adjuvant. It is currently approved in Canada for those ages 18-64, and clinical trial data demonstrated efficacy of 71% against symptomatic illness. However, this clinical trial was conducted prior to the emergence of the Omicron variant, so we do expect some potential adjustments moving forward.

Additional contributors: