COVID-19 Status Update: Part 1

Abysmal vaccine uptake, infection surge may be receding, and more...

What’s the status report on COVID-19?

Most public health experts agree that we are currently in the second-largest wave of COVID-19, (second to the omicron surge in late 2021 and early 2022). Are we still in a pandemic? If you ask us, the answer is yes, unfortunately– though we are not in the acute stage of the pandemic that we were a couple of years ago.

Abysmally low vaccine uptake, waning immunity, and holiday gatherings likely contributed to the recent spike in cases.

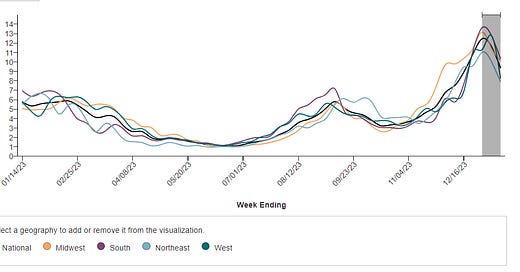

Since the number of cases and positive test results are no longer being consistently reported and tracked, public health surveillance of COVID-19 now relies on wastewater data to provide our best estimate of disease prevalence in our population.

We did a post on wastewater surveillance if you need a refresher. (Briefly: people who are infected with SARS-CoV-2 shed virus in their feces whether they know they’re infected or not. Therefore, viral RNA can be isolated and detected in wastewater samples, enabling us to monitor prevalence and genetics of SARS-CoV-2 on a community-level basis. Wastewater surveillance can provide early warning that COVID-19 is spreading within a population).

The CDC launched the National Wastewater Surveillance System (NWSS) in September 2020. CDC developed NWSS to coordinate and build the nation’s capacity to track the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater samples collected across the country.

Biobot Analytics does a great job charting the latest data by geographic region if you wish to explore further (you can even filter down to the county-level).

There are some notable limitations of wastewater surveillance including the lack of standardization across testing sites. Other issues:

Cannot provide individual-level information. Samples are from sewage, so it can only look at trends within samples over time, and cannot provide any information about households or individuals.

Participation fluctuates: the number of reporting sites varies over time, with peaks in August 2023 and January 2024 (there are currently around 800 sites reporting).

Uneven coverage: Some states like California and Ohio report regularly, while others like Oklahoma haven't reported in months.

Urban bias: Data are better collected in cities and towns, but less available in rural areas.

Septic systems excluded: About 20% of US households use septic systems, which wastewater surveillance can't track.

For these reasons, we won’t spend too much time analyzing specific wastewater estimates– instead, we are looking for overall trends. The good news is that we seem to be coming down from a late-December/early-January peak in cases.

We tend to focus our efforts on healthcare utilization as a measure of disease burden (and to gauge our healthcare system’s resources and ability to manage the ongoing pandemic). Not surprisingly, ED visits and hospitalizations surged in late-December and early January– and have come down in recent weeks. Some key metrics: 2.5% of emergency room visits were among people diagnosed with COVID-19 (down 19% from last week), and about 33,000 people were admitted to the hospital with COVID-19 this week (down 10% from last week). Looking at mortality, 4.3% of all deaths in the US this past week were attributed to COVID-19. This represents a 10% increase from last week but, remember, there’s a lag for mortality data– so this is not surprising.

What else do we know?

No surprise here: the latest CDC genomic data today indicates the JN.1 variant of SARS-CoV-2 has taken over as the dominant strain. If you recall, JN.1 first cropped up onto our radar around September 2023.

We know other SciComm pages have shared somewhat alarming headlines, but we don’t freak out when a new variant becomes a dominant strain: this is the nature of viral mutation that leads to antigenic drift.

What is antigenic drift? Here’s a very high-level summary:

Mutations occur as a result of random errors during viral replication. The rate of viral replication is a direct result of how many people are infected. Thus, the more viral spread that occurs, the more viral replication, the faster the rate of mutation, and the more likely potential mutations may emerge.

Some mutations change the virus's spike proteins, the "keys" it uses to unlock and enter our cells (the spike protein is a key antigen of SARS-CoV-2, which is what we target with the COVID-19 vaccine).

If these mutations make it more difficult for our immune system to target and neutralize the virus, it may spread more easily and outcompete other strains in the population.

Why do new variants often become dominant? We have done a few posts on this, here is one example.

Immune escape: If a new variant has mutations that allow it to better avoid our immune system defenses (the guards being fooled by the slightly different uniforms), it will have a survival advantage over a previous strain. As a result, it will be able to infect more people and spread faster.

Increased transmissibility: Some mutations might make the virus more contagious, even if they aren’t allowing it to avoid immune defenses more effectively. This can also help it become dominant. These can be related to replication rate, survival in the environment, etc.

Competition: Different variants are constantly competing for resources and opportunities to infect. Those with the best combination of immune evasion, transmissibility, and other factors will outcompete the others and become more common.

Is the JN.1 variant any different in terms of clinical illness?

The good news is that JN.1 does not seem to cause more cases of severe disease or symptoms that differ from those associated with previous strains. The CDC has noted that COVID-19 symptoms have tended to be similar across variants, and symptoms and severity are usually more dependent on the person’s immunity than they are on the variant.

Some media outlets have reported anecdotally that there are more gastrointestinal issues with this variant (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea), but that isn’t well-supported with data. Some doctors have reported that upper respiratory symptoms seem to follow a pattern of starting with a sore throat, followed by congestion and a cough– but, again, there are no set patterns and symptoms (and symptom severity) have a lot more to do with our individual immune systems than the circulating variants.

What’s this I heard about a new SARS-CoV-2 variant that is 100% lethal?

We are shaking our heads right now – because the media outlets have done some seriously irresponsible reporting on this topic. For starters: NO - the Chinese government is not actively engineering more dangerous viruses and SARS-CoV-2 variants. A pre-print was taken wildly out of context and has led to some undue fear (by the way, it has since been updated here). Let’s keep it super short and sweet: news articles are referring to a coronavirus found in Pangolins called GX_2PV which was discovered back in 2017. Scientists have been studying this (and many other coronaviruses over the last several decades) to further our understanding of the risks they pose to human health and further the development of vaccines.

So, scientists bred mice to express high levels of the human ACE2 protein (this is the receptor on our cells that the virus attaches to in order to infect) to see how they would respond when exposed to this virus. Four of the mice exposed to the virus and infected died. As we ALWAYS say, preclinical (animal) studies do NOT necessarily translate to humans, especially in this case because the mouse models developed do not appropriately model the human response (for a variety of super technical immunological reasons).

There is no reason to freak out. Virology research is always ongoing, and is critical to understand viruses as well as the immunology and pathology behind infections.

Stay tuned for part 2 tomorrow, where we will discuss long COVID, vaccines, and what you can do continue to reduce the spread of infection and manage symptoms if you get sick.

In the meantime though: vaccine uptake is ABYSMAL.

As of January 6, 2024, 21.4% of adults reported having received an updated 2023-24 COVID-19 vaccine since September 14, 2023. As of December 30, 2023, 8.0% of children were reported to be up to date with the 2023-24 COVID-19 vaccine.

Reminder: Anyone 6 months and older can (and should) get the new COVID-19 vaccine.

It does not matter how many doses you’ve received previously.

The new vaccine is effective against currently circulating strains. We have heard people say that they can’t find a vaccine local to them (this is very upsetting– and it’s largely due to the fact that because we are no longer in a public health state of emergency, funding for vaccines has changed– and many pharmacies and doctor’s offices are scared to order vaccines only to have them go unused (aka wasted money).

Some tips:

Check vaccines.gov

Contact your local department of health; they may run vaccine clinics or have suggestions for other community health organizations offering vaccines

Ask your pediatrician for recommendations

For those who do not have insurance that covers COVID-19 vaccines (or lack coverage altogether): CDC’s Bridge Access Program provides free COVID-19 vaccines to adults without health insurance and adults whose insurance does not cover all COVID-19 vaccine costs.

One final ask: if you are a healthcare provider, please add yourself to our HCP listserv! Find it here.