Are We in the Bad Place?

How scientists and MAHA supporters both think they're protecting children—while convinced the other side is causing harm

(The Good Place spoilers ahead…)

Remember that gut-punch moment at the end of The Good Place's first season? When Eleanor suddenly realizes they've been in the Bad Place all along, being tortured while genuinely believing they were in paradise? Everyone was so convinced they were in the right place, working toward good outcomes, completely unaware that their reality was fundamentally different from what they thought.

Well, holy forking shirtballs, folks… that's exactly where we are with health and science in America right now.

Two Realities, Same Goal

I've been watching the conversations around the MAHA movement and the scientific establishment, and it's like watching two groups of people who are absolutely convinced they're living in the Good Place while viewing the other side as clearly residing in the Bad Place.

In the MAHA reality: They're the heroes fighting for health freedom, protecting children from harmful chemicals in food, questioning the overuse of medications, and taking on corrupt institutions that prioritize profits over people. The scientists and public health officials? They're either captured by pharmaceutical companies or willfully blind to obvious harms, essentially torturing children with processed foods and unnecessary interventions.

In the science establishment reality: They're the heroes protecting public health through rigorous research, evidence-based medicine, and hard-won gains against preventable diseases. They're defending scientific integrity and saving lives. The MAHA supporters? They're spreading dangerous misinformation that threatens decades of progress and puts vulnerable populations at risk.

Here's the thing that keeps me up at night: Both sides genuinely want the same thing. Healthy kids. Thriving communities. An end to chronic disease. They're not cartoon villains twirling their mustaches. They're parents, doctors, researchers, and advocates who started from the same place of caring.

The Data Means Different Things to Different People

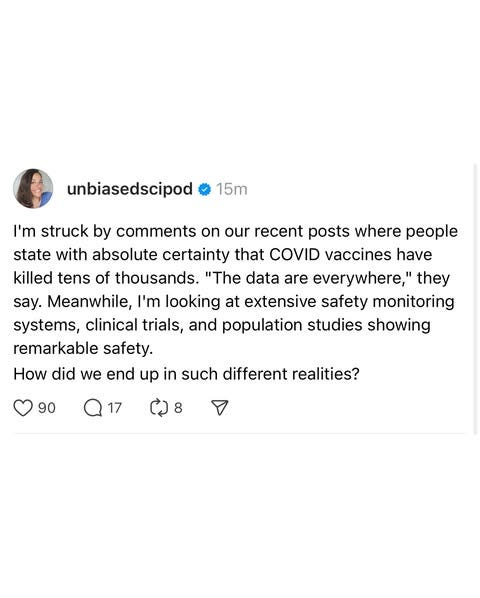

What's mind-bending is watching the same information get processed through these two different realities and come out meaning completely opposite things.

When MAHA supporters point to rising rates of childhood chronic illness, they see evidence of a system failing kids through environmental toxins and overmedication. When scientists look at the same data, they see the success of better diagnostic tools and the urgent need for more research and evidence-based interventions.

When the scientific community points to vaccine safety monitoring systems catching rare adverse events, they see proof the system is working. When MAHA supporters see the same reports, they see evidence that vaccines are dangerous and the risks are being downplayed.

It's not that one side is looking at data and the other isn't. They're both looking at data. They're just living in fundamentally different realities about what that data means.

And here's where I have to be honest about my own perspective: as a scientist, I'm trained to differentiate between hazard and risk, to understand the complexities of health outcomes, and to resist oversimplified causation. I know that if you look hard enough, you'll find a study supporting almost any conclusion you want to reach—but not all studies are created equal. This training shapes how I process information in ways that create genuine differences in how we evaluate evidence.

But when I try to explain why study quality matters, or why we might prioritize addressing poverty over food dyes when it comes to childhood health outcomes, it often gets interpreted as me being captured by corporate interests rather than applying scientific training. The response becomes: "How can you defend artificial dyes? You must be funded by Big Food!" when really I'm trying to say: "Given limited resources and attention, shouldn't we focus on the interventions with the strongest evidence for the biggest impact?"

The Exhaustion Is Real

Unlike The Good Place, there's no Michael figure who's going to reveal which reality is actually correct. And honestly? The constant fighting is wearing everyone down.

I see well-intentioned people on both sides getting increasingly frustrated, exhausted by trying to bridge-build when every attempt at good faith conversation gets interpreted through the other side's reality as manipulation or willful blindness. The MAHA supporters feel dismissed and attacked when they raise concerns. The scientists feel like they're fighting misinformation while their expertise is being undermined.

And with each failed attempt at dialogue, both sides retreat further into their own information ecosystems, more convinced than ever that the other side represents an existential threat.

The Trust Problem

Here's what makes this so much harder than a TV plot twist: This isn't really about the science anymore. It's about trust.

The MAHA movement gained momentum during the pandemic when many people felt misled about vaccine effectiveness and frustrated by changing guidance. The scientific establishment is dealing with institutions that have lost credibility with large portions of the public. When trust breaks down this fundamentally, even perfect evidence can't bridge the gap.

But the trust breakdown creates impossible binds. When scientists try to explain why we might prioritize research on structural inequities over investigating every possible environmental exposure, it gets heard as dismissing legitimate concerns. When we point out that correlation doesn't equal causation, or that study methodology matters, it sounds like gatekeeping.

And when MAHA supporters raise concerns about corporate influence on research—which is a real issue scientists worry about too—any nuanced response gets flattened into: "See? They're defending the system because they're part of it."

Each side sees the other's skepticism as proof of their moral failings. Scientists see MAHA supporters as falling for cherry-picked studies and oversimplified causation. MAHA supporters see scientists as captured by corporate interests or so embedded in the system they can't see its flaws. And round and round we go.

Where Do We Go From Here?

I don't have a neat solution, because unlike The Good Place, this isn't a philosophical thought experiment. Real policies are being made. Real health decisions are being influenced. Real children's futures are at stake. Everything’s not fine.

Let me be clear: this isn't some kumbaya moment with easy solutions. While we're having these philosophical debates, real policies are being torn down and erected. Research funding is being slashed. Entire institutes are disappearing. There's a battle being fought, and I won't pretend otherwise.

And yes, I am livid. Yes, I often want to scream. Taking a tempered approach is not easy when you're watching the public health and science establishment crumble. But what does screaming accomplish? There's a time and a place for righteous anger—we're human, we're feeling strong emotions. But what is our goal?

There are bad actors in both camps: people without health or science backgrounds leading health and science institutions, grifters exploiting legitimate concerns for profit, ideologues more interested in being right than in better outcomes.

But here's where we in science need to practice what we preach: just as we always say that things aren't black and white, we need to accept that nuance in people too. Someone can take herbal supplements without being an "anti-science conspiracy theorist" we should dismiss. A mother who chooses not to vaccinate her child genuinely thinks she's making the right decision for her family, even if we disagree with her risk calculation.

Our job isn't to shame her—it's to ensure she's making that decision based on credible information, not a misinformation bot account named "s@yNOtotheCLOTSHOT."

The question isn't whether we abandon scientific rigor—we can't and shouldn't. It's whether we can engage with underlying concerns while still maintaining our standards for evidence.

The tragedy isn't that we disagree about solutions. The tragedy is that we've become so convinced the other side is fundamentally wrong or corrupt that we've stopped trying to understand what they're actually worried about underneath all the talking past each other.

We all started wanting healthy, thriving kids and communities. But we've become so entrenched in fighting each other that we risk losing sight of that shared goal entirely. The tragedy isn't just that we disagree—it's that we might all lose while we're busy proving we're right.

The question isn't who's right. The question is: Can we find a way to fight for evidence-based solutions without losing the people we need to reach? How do we maintain scientific integrity while acknowledging that dismissing everyone who questions the system isn't working?

I don't know the answer. But I do know that if we keep treating this like a zero-sum battle where one side must completely defeat the other, we'll all end up in the actual Bad Place—a world where children suffer while the adults who care about them are too busy fighting to notice.

Stay Curious,

Unbiased Science

P.S. Want to support our work? The best way is to subscribe to our Substack and share our content. While all our articles are always completely free to read, paid subscriptions help sustain our in-depth reporting on public health and science topics. Thank you for considering it!

A sad and dangerous reality is that the MAHA side has unfettered access to the eyes and ears of anyone with a television while the voices for science only have access to people who are willing to dig for and consider the evidence.

What I’m seeing in practice at the bedside seems to be a fundamental shift in how we view knowledge and how we can know things. Many families now don’t care about data and are much more invested in what someone’s experience is, especially someone they know and trust. So if a neighbor says their child was diagnosed with autism after vaccines, then they conclude a causal relationship and no amount of data or stats can change that opinion. It’s just a totally different language and as you note the scientific community needs to understand that throwing studies and data at people won’t stick. We need more medical and scientific professionals to talk earnestly about their experiences. I usually talk about the children I’ve cared for with vaccine preventative diseases and how they suffered. But it’s very frustrating and the leaders of these misinformation fountains on social media are so difficult to compete with because of the volume and prevalence.