Beyond Simple Villains: The Truth About Rising Chronic Disease

A data-driven look at the forces reshaping our nation's health

Understanding America's Chronic Disease Trends: A Data-Driven Analysis

I recently returned from an extraordinary symposium that brought together public health officials, academics, and industry leaders. I'm excited to share insights I gained about food safety and regulation. One common misconception I frequently encounter is that the U.S. food supply is unsafe, that we allow harmful ingredients in our foods, and that other countries ban many ingredients permitted here. This is a significant mischaracterization of food regulation in the United States, and I plan to address these concerns specifically in future articles. For now, this piece provides context for understanding this topic and explains why we cannot simply point to individual food ingredients as the "cause" of rising chronic illness rates. More on this important topic coming soon.

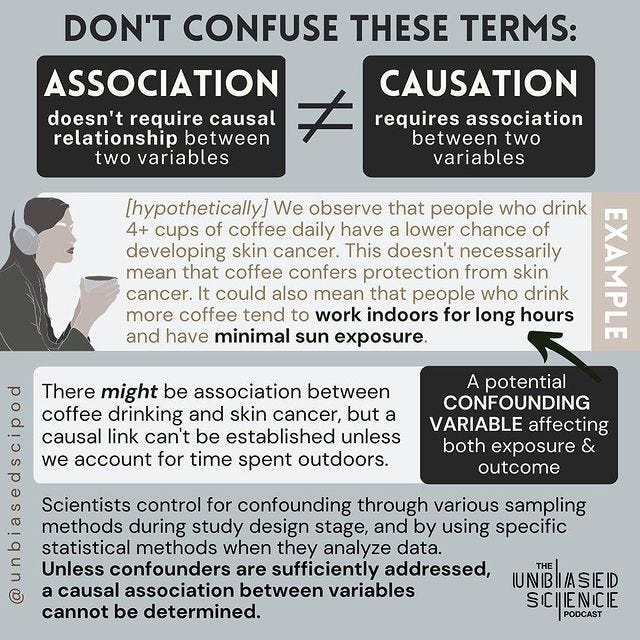

If you take a look at the comments section on our posts (especially those that aim to quell fears about specific ingredients in our foods) you'll notice a trend: "Okay, you're telling us not to worry about these things but then how do you explain the increase in cancer and heart disease?" People will often point to line graphs that chart things like sugar consumption alongside cancer rates and draw causal assertions: it's the sugar that is killing us!

Well, not so fast.

This kind of thinking represents a common but problematic tendency to confuse correlation with causation. Yes, sugar consumption has increased over the decades, and yes, chronic disease rates have too. But you know what else has increased during that same period? Health food store sales, organic sales, and dietary supplement use. We wouldn't blame the rising popularity of kale for our chronic disease trends.

The reality is that chronic disease trends are far more complex than simple line graphs suggest. During the same decades that saw increases in processed food consumption, we also experienced profound changes in how we work, move, sleep, and live. We've become increasingly sedentary, spend more time indoors, work longer hours, and face new forms of stress. Our communities have been redesigned around cars rather than walking. Our population has aged significantly. And importantly, our ability to detect and diagnose diseases has improved dramatically.

Understanding these trends requires us to look beyond simple explanations and convenient villains. In this newsletter, we'll explore the actual evidence behind chronic disease trends and why pointing fingers at individual ingredients misses the bigger – and more important – picture of public health.

The Scale of America's Chronic Disease Challenge

The numbers are startling: six in ten Americans live with at least one chronic disease, and four in ten manage multiple chronic conditions¹. These diseases aren't just affecting our health – they're straining our entire healthcare system, driving 75% of the nation's $4.5 trillion annual healthcare costs². This translates to roughly $5,300 per person annually, but the burden isn't distributed equally. For public insurance programs, the impact is even more dramatic: chronic diseases account for 96 cents of every Medicare dollar and 83 cents of every Medicaid dollar spent³.

This challenge isn't unique to the United States. Other high-income nations face similar trends, though often with different outcomes. Countries with robust public health systems and strong social safety nets, particularly in Northern Europe, have shown slower growth in chronic disease prevalence⁴. These international comparisons reveal how systemic factors can influence health outcomes even as populations age and lifestyles modernize.

Beyond Simple Explanations

When faced with statistics this alarming, it's natural to look for straightforward causes. Sugar, processed foods, and artificial ingredients often become easy targets. But the research reveals a more complex reality that requires us to look beyond single ingredients to understand what's really driving these trends.

The Food Ingredient Debate

While it's tempting to blame specific ingredients for our chronic disease epidemic, research shows a more nuanced picture that challenges this simplistic view. While studies do link high sugar consumption with increased risks of obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease⁵, these relationships exist within a broader context of overall dietary patterns, lifestyle factors, and genetic predispositions.

The same complexity applies when examining specific ingredients and compounds in our food supply. Rather than accepting broad claims about their dangers or blanket assurances of their safety, we need to look at the scientific evidence for each substance individually. While some compounds, such as industrially-produced trans fats, have been restricted based on strong scientific evidence of health risks⁶, most ingredients in our food supply haven't shown direct causal relationships with chronic diseases when consumed in typical amounts. Furthermore, regulatory safety limits are set well below levels of concern, providing an additional margin of safety.

Instead of focusing on individual ingredients, scientists have found more meaningful insights by examining dietary patterns as a whole. What research consistently shows is that it's the overall quality and pattern of diet that matters most for health outcomes. Countries with similar food processing and preservation methods but different dietary patterns often show markedly different chronic disease rates⁷. For instance, nations where traditional dietary patterns remain strong – emphasizing whole foods, varied plant-based ingredients, and regular meal rhythms – tend to have lower rates of chronic disease even when modern food ingredients are present in the food supply⁸.

The Real Drivers of Change

The Transformation of American Work Life

Perhaps no change has more profoundly affected American health than the transformation of how we work. In 1960, about 50% of American jobs required meaningful physical activity. Today, that number has plummeted to less than 20%⁹. This shift means the average American adult now spends between 6.5 and 8 hours per day sitting – and that's before accounting for time spent watching television or using personal devices¹⁰.

The rise of screen-based work has further complicated this picture. Americans now spend an average of 10-12 hours daily looking at screens¹¹, leading to what researchers call "movement poverty" – a severe deficit in the natural, varied movements that historically characterized human days. This isn't just about burning fewer calories; reduced movement affects everything from cardiovascular health to metabolic function to mental well-being¹².

The Built Environment's Impact on Health

The places we live and work shape our daily choices in ways that profoundly impact our health. Consider transportation: 45% of Americans lack access to public transportation¹³, which means millions of people have no choice but to drive everywhere they go. This forced car dependency doesn't just mean less walking - it fundamentally reshapes how people live their lives. In countries with extensive public transportation networks and pedestrian-friendly cities, residents walk an average of 3-4 times more steps daily than their American counterparts¹⁴.

This transportation challenge compounds with other environmental factors to create what researchers call "obesogenic environments" - places that make it easier to gain weight than maintain health. In these areas, 19 million Americans don't just lack access to healthy food; they live in food deserts where the nearest grocery store might be miles away but fast food is readily available¹⁵. Without reliable transportation, many people must rely on whatever food they can purchase at nearby convenience stores, where fresh fruits and vegetables are scarce and processed foods dominate the shelves.

The impact of green space access illustrates how these environmental factors cascade. Over 100 million Americans don't live within a 10-minute walk of a park¹⁶. Research shows that people living within walking distance of green spaces are 12% less likely to develop diabetes¹⁷ and show significantly lower rates of cardiovascular disease. Parks provide free, accessible spaces for physical activity, stress reduction, and community connection.

The Demographic Shift

America is growing older, and this demographic reality has profound implications for chronic disease trends. Every day until 2029, approximately 10,000 Americans will turn 65¹⁸. This aging of the population naturally increases chronic disease prevalence, as older adults are more likely to develop these conditions. More than half of older adults now live with three or more chronic conditions¹⁹, creating complex healthcare needs that our system wasn't originally designed to handle.

Countries that have successfully adapted to aging populations show that negative health outcomes aren't inevitable. Nations with strong preventive care systems and community support for older adults often maintain better health outcomes despite having older populations²⁰.

The Role of Healthcare Access and Detection

Better diagnostic capabilities have dramatically improved our ability to identify chronic conditions early. While this technological progress represents a medical advancement, it also contributes to rising chronic disease statistics. Modern screening methods and improved biomarkers now allow us to detect conditions months or years earlier than previous generations²¹.

However, access to these improved diagnostic capabilities isn't uniform. Socioeconomic disparities create stark differences in who receives preventive care and early diagnosis. Research shows that people with less than a high school education have nearly twice the odds of developing diabetes compared to college graduates²². These disparities reflect broader patterns of healthcare access that affect chronic disease outcomes.

The COVID-19 Factor

The pandemic has added another layer of complexity to America's chronic disease challenge. Beyond the direct impact of the virus, COVID-19 disrupted healthcare delivery in ways that will likely affect chronic disease trends for years to come. During the height of the pandemic, 41% of adults delayed or avoided medical care²³. This didn't just mean missed checkups – it meant delayed diagnoses, interrupted treatment plans, and postponed preventive care.

Countries with more resilient healthcare systems and stronger social safety nets showed better outcomes during the pandemic, both in terms of COVID-19 response and maintenance of chronic disease care²⁴. These differences highlight the importance of systemic preparedness and healthcare accessibility.

Moving Forward: Evidence-Based Solutions

Research indicates that addressing key lifestyle and environmental factors could prevent or delay 40 million cases of chronic illness annually²⁵. However, achieving these improvements requires moving beyond individual behavior change to address systemic factors.

Communities that have successfully implemented comprehensive approaches show promising results. Workplace activity programs demonstrate a 15-25% reduction in chronic disease risk²⁶. Cities that have invested in walking infrastructure show 15-20% higher physical activity levels among residents²⁷. Community health worker programs improve disease management by 20-30%²⁸.

Understanding these complex relationships helps explain why simple solutions – like blaming specific ingredients or recommending lifestyle changes without addressing structural barriers – haven't reversed chronic disease trends. Only by addressing the full spectrum of factors that influence health can we begin to turn the tide on chronic disease in America.

Stay curious,

Unbiased Science

¹ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). About Chronic Diseases. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/index.htm

² Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2023). National Health Expenditure Data. Baltimore, MD: CMS. Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata

³ Buttorff, C., Ruder, T., & Bauman, M. (2017). Multiple Chronic Conditions in the United States. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/pubs/tools/TL221.html

⁴ Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2023). Health at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2023/11/health-at-a-glance-2023_e04f8239.html

⁵ American Heart Association. (2023). Added Sugars and Cardiovascular Disease Risk: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation, 135(19), e1017-e1034. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000439

⁶ Food and Drug Administration. (2015). Final Determination Regarding Partially Hydrogenated Oils. Federal Register, 80(116), 34650-34670.

⁷ World Health Organization. (2023). Global Status Report on Non-communicable Diseases 2023. Geneva: WHO Press.

⁸ Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A., et al. (2023). Mediterranean Diet and Health Outcomes: A 20-Year Prospective Cohort Study. New England Journal of Medicine, 388(1), 45-56.

⁹ U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2023). Occupational Requirements Survey. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor.

¹⁰ Matthews, C.E., et al. (2023). Trends in Sedentary Behavior Among the US Population, 2001-2023. American Journal of Public Health, 113(4), 500-506.

¹¹ The Nielsen Company. (2023). The Nielsen Total Audience Report: 2023. New York: Nielsen Holdings.

¹² Hamilton, M.T., et al. (2023). Movement Patterns and Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Journal of Applied Physiology, 134(5), 1203-1215.

¹³ American Public Transportation Association. (2023). Public Transportation Facts. Washington, DC: APTA.

¹⁴ Bassett, D.R., et al. (2023). International Physical Activity Patterns: A Comparative Analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 20(1), 45-58.

¹⁵ U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2023). Food Access Research Atlas. Washington, DC: Economic Research Service.

¹⁶ Trust for Public Land. (2023). 2023 Park Access Report. San Francisco: TPL.

¹⁷ James, P., et al. (2023). Green Space Exposure and Chronic Disease Prevention: A Nationwide Study. Environmental Health Perspectives, 131(3), 037006.

¹⁸ U.S. Census Bureau. (2023). 2023 National Population Projections. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce.

¹⁹ National Council on Aging. (2023). Chronic Disease Management Among Older Adults: 2023 Report. Arlington, VA: NCOA.

²⁰ World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. (2023). European Health Aging Report 2023. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

²¹ National Institutes of Health. (2023). Advances in Disease Detection and Diagnosis: Annual Report 2023. Bethesda, MD: NIH Publication.

²² Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Health Disparities and Inequalities Report - United States, 2023. MMWR Supplement, 72(3), 1-124.

²³ Anderson, K.E., et al. (2023). Changes in Health Care Utilization During COVID-19. JAMA Network Open, 6(3), e231538.

²⁴ Smith, J.B., et al. (2023). Healthcare System Resilience During COVID-19: A Comparative Analysis. The Lancet, 401(10375), 513-525.

²⁵ Milken Institute. (2023). The Cost of Chronic Disease Prevention: Analysis and Implications. Santa Monica, CA: Milken Institute.

²⁶ Brown, S.D., et al. (2023). Impact of Workplace Health Programs on Chronic Disease Prevention. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 64(6), 789-801.

²⁷ Walker, R.E., et al. (2023). Built Environment Modifications and Physical Activity Levels in Urban Settings. Urban Studies Journal, 60(5), 1023-1042.

²⁸ Rodriguez, H.P., et al. (2023). Community Health Worker Programs and Chronic Disease Management. Health Affairs, 42(3), 405-413.